Across Desert Trails and Rocky Shores: A Learning Cluster Takes Students Into Southern California’s Ecosystems

As the rotating tram car steadily climbed 8,500 feet to Mountain Station on Mount San Jacinto, the small group of SUA students inside watched in wonder while the landscape beneath them shifted from desert canyon to alpine forest.

“When you go up the mountain, you can see snow, forest, and water cutting through,” said Christian Obergfell ’29 of Rockland County, New York. “The elevation has an effect, and the whole ecosystem is different.”

Obergfell and his classmates were on a field trip as part of a Learning Cluster taught by Robin Fales, assistant professor of marine ecology, on the natural history and ecology of Southern California. A cornerstone of education at SUA, Learning Clusters are intensive 3.5-week courses that engage students with real-world issues through hands-on learning experiences. Taking place in January prior to the start of the spring semester, the focused schedule and small class sizes enable these seminars to travel regionally or even internationally to immerse students in a topic.

Fales’s Learning Cluster took advantage of Southern California’s uniquely diverse geography to help students learn about five distinct biomes: deserts, alpine forests, chaparral, estuaries, and rocky intertidal zones. Students studied the plants, animals, climate, and geology of each region before experiencing them in person. In addition to Palm Springs and Mount San Jacinto State Park, the class visited Irvine Regional Park, the Upper Newport Bay Nature Preserve and Ecological Reserve, and Shaw’s Cove in Laguna Beach.

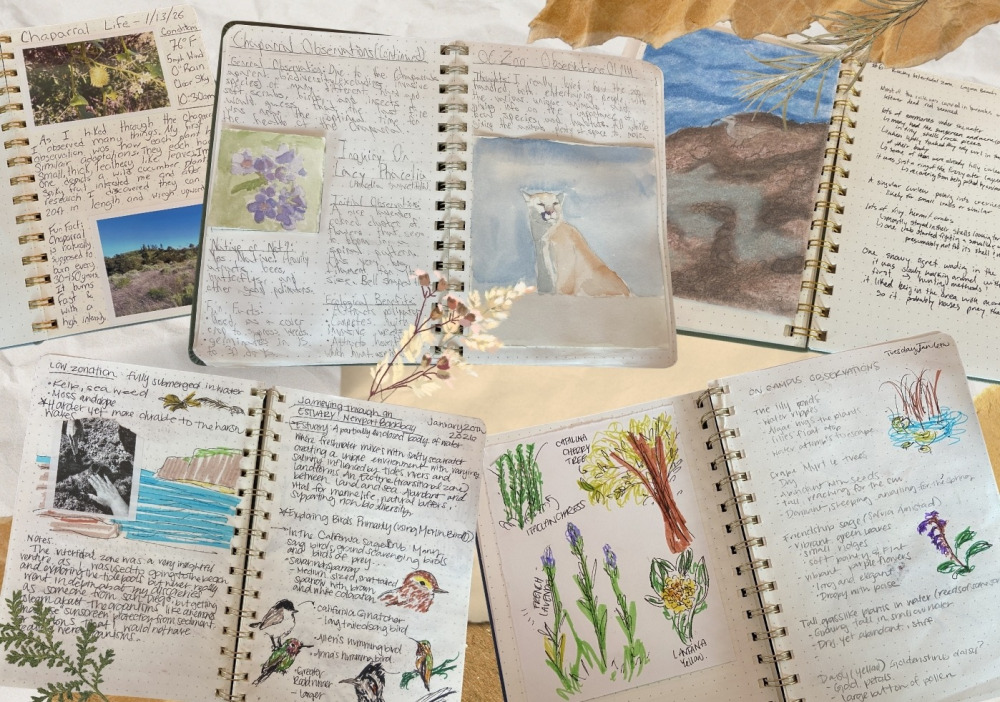

At each site, students collected ecological data using scientific surveying techniques. They also explored independently and recorded their observations in natural history journals. The latter activity is at the heart of the course, which asks students to slow down and carefully observe organisms in their environment. While this kind of natural history practice is often deprioritized in scientific research today, Fales said, it remains crucial to understanding how species live and interact within ecosystems.

In their journals, students not only described what they saw and noted thoughts and reflections; they also represented their observations through creative media such as poetry, fine-art photography, pencil or ink drawings, pastel illustrations, or watercolor paintings. A great example of the interdisciplinarity at the core of Learning Clusters and education at SUA, this activity allowed multiple points of entry into the subject matter and benefited students with wide-ranging academic interests.

The course also encouraged students to make connections between their local ecological knowledge and global environmental issues, diving into topics in nature conservation and habitat restoration that are relevant to biomes around the world.

“There are so many lessons to be learned in Southern California that we can apply globally,” Fales said. “When we examine issues like overfishing or fire frequency, we also talk about how this can apply to other ecosystems.”

The class engaged in many discussions about human environmental impact and compared the success of different conservation efforts.

“It was really interesting to learn about how the same human intervention can have negative or positive effects in different biomes,” said Keegan Nichols ’28 of Johnstown, Colorado. “Each ecosystem has its own needs.”

Among the most impactful experiences for students was an ecological survey of the tide pools at Shaw’s Cove. Teams of students spread out across the rocks, laid out transect (measuring) tape, and counted all the organisms within 625 square centimeters.

“I felt like a scientist while I was doing it, peeling away the seaweed and really looking at everything there,” Obergfell said. He found it especially meaningful when, back in the classroom, they put together the data they had collected in the field and analyzed how species coverage changes from the tide pools’ low zones to the middle and high zones.

Students also tried their hand at timed surveys during their field trip to Upper Newport Bay, where they recorded all the birds they saw and heard within a set amount of time. Isabella Shelton ’29 of Huntington Beach, California, particularly enjoyed identifying birds using the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Merlin app. Along with a few of her classmates, she has continued using the app around SUA’s campus.

“I’ll take a second, listen to a bird, and try to figure out what bird it is,” Shelton said. “I didn’t do that very often before. It’s nice to get a new perspective.”

This perspective shift, Fales said, was part of the purpose of the birding activity –– and the Learning Cluster as a whole.

“It helps students realize that there is a lot more wildlife around them,” she said, “especially on our beautiful campus, which is next to a canyon with a lot of natural habitat.”

For Shelton, a defining moment of the course occurred during a hike in a preserve near Palm Springs, where Fales directed the class’s attention to the fan palms. Unlike the palm trees students are used to seeing in landscaped areas around Orange County, the trunks of these trees were covered in layers of dead fronds reaching nearly to the ground. In a protected area, Fales had explained, the dead fronds are left on palm trees because they are an important habitat for birds.

“Little tidbits like that really make you think more deeply about the human impact on the environment,” Shelton said. While Shelton was already planning to concentrate in environmental studies prior to taking the Learning Cluster, she now feels especially confident in that choice.

The course has also left a lasting impression on classmates taking different academic paths. Obergfell, who is concentrating in life sciences and plans to pursue a career in medicine, has been inspired to potentially incorporate environmental research questions when he begins his senior capstone in a couple of years.

As a humanities concentrator, Nichols plans to use his ecological knowledge to enrich his understanding of art history. The Learning Cluster has also given him new tools for observing nature that he can bring into his own art practice, and he is looking forward to doing more plein air painting.

For Fales, this type of academic exploration and self-reflection makes Learning Clusters an invaluable part of education at SUA.

“I really like that Learning Clusters are early on in students’ academic paths,” she said. “Students do them in their first and second years. It’s something that allows them to dive into their interests and think about how they want to grow as a student and as a person.”