From Office Hours to Published Book: Faculty-Student Collaboration Spans a Decade

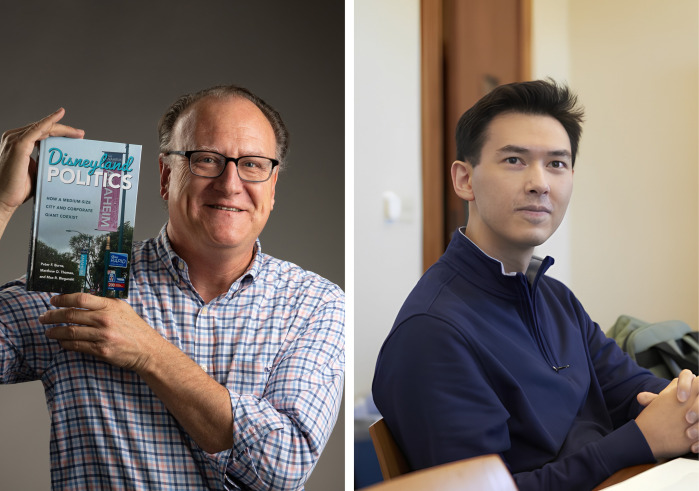

When Max Bieganski ’19 M.A. ’22 walked into Professor of Political Science Peter Burns’ office during their first week at SUA, neither knew that it would be the start of an intellectual partnership culminating in a co-authored book.

Bieganski was participating in Scholar’s Peak, a campus housing program in which a professor in residence mentors a group of first-year students. In fall 2015, that professor was new faculty member Peter Burns. As Burns and Bieganski recalled in a recent interview, Burns had invited the Scholar’s Peak students to stop by during his office hours.

“Max showed up the next day,” Burns said, “and as I like to say, he left six or seven years later … Max was the first person I really knew at Soka.”

More than a decade after that first conversation, Temple University Press has published “Disneyland Politics: How a Medium-Size City and Corporate Giant Coexist,” written by Burns, Bieganski, and fellow co-author Matthew Thomas, professor of political science and criminal justice at California State University, Chico.

The book is a fascinating study of the changing relationship between Disneyland and the city of Anaheim over the theme park’s 70-year history. The book fills a notable gap in political science scholarship, which tends to focus on the nation’s largest cities and overlook the unique lessons of how a smaller, more resource-strapped city like Anaheim can balance the interests of its residents with that of a corporate giant like Disney — especially when those interests conflict. The Los Angeles Times covered the book’s release in December.

In the following conversation, Burns and Bieganski reflect on their research and how SUA’s educational environment made their collaboration possible.

Could you share the story of how you became a research team and started working on this book?

Bieganski: I began working as Peter Burns’ research assistant during my first year. I helped him with research and preparing class activities. My second year, Peter taught a Learning Cluster about the politics of Disneyland. This course focused on the content of the theme park itself, as well as the park’s relationship with the city of Anaheim and the Disney corporation. That was the genesis of this book project.

Burns: I didn’t come to Soka thinking that I was going to write about this topic, but I remember constantly speaking with Max about it. It was very clear to me that Max was an excellent thinker with a very strong academic pulse.

Max was involved in every step of this project from day one. He was my research assistant for four years. And then he went to graduate school at Soka, and we continued having these discussions. I would call him nearly every day to talk about the project and bounce ideas off each other. During COVID, we conducted every interview together over the phone. I would tell the interviewee, you had better be careful, because the hardball questions are going to come from Max at the end.

The third author, Matthew Thomas, joined this project a little later. But Max and I started this project at Soka. It was very much a Soka project.

Is there something special about SUA that enables this kind of research collaboration between faculty and students?

Bieganski: Yes, absolutely. The close relationships you can cultivate with the faculty are one of the main benefits of going to a small university like this one. Soka education promotes developing a connection with your mentor, getting to know them, and continuing that relationship over time. That’s something Soka does uniquely well.

Burns: At Soka, it’s very normal for faculty and students to interact. I like working with students, and it is so accessible here — especially when I lived on campus during my first two years. I don’t mean to exaggerate, but I think I ate just about every one of my meals with Max.

SUA’s research assistant program was also vital to this project, because students who were my research assistants after Max helped me, too. Max went to three conferences with me. When he presented our research at a conference in San Diego, a couple faculty members asked us great questions, and answering those questions became our North Star. I thought that was an invaluable experience.

Bieganski: The teaching style and the academic culture at Soka is also very conducive to developing research skills. Resources like travel funding enabled me to go to conferences, give a talk, and meet fellow scholars. Soka teaching often emphasizes developing speaking skills in front of a class. Perhaps because of larger class sizes, it’s not as common for students at other universities to give presentations in a small context that mimics a conference presentation.

Another way I benefitted from being a Soka student is learning to have empathy for different perspectives. As Peter mentioned, we did interviews as part of our book project. Some people think Disneyland is very beneficial to the city of Anaheim, supposedly bringing in a lot of revenue for the city. Others say that the people who live and work there aren’t getting their fair share and that most of the profits are going to corporations and Disney stakeholders. I’m not sure I can say whether one side or the other is right — and perhaps it’s not my role to say that. But being a Soka student gives you the skills to have dialogue with people, understand their perspective, and then translate that for others and bridge gaps in understanding.

Do you think SUA’s emphasis on the liberal arts and interdisciplinary inquiry played a role in the types of questions you asked in this research and how you went about answering them?

Burns: Studying cities, you have to be multidisciplinary because you’re talking about sociology, policy, government, and law. Max would bring a quantitative perspective to the project. He benefited a lot from his environmental studies classes, especially a course on international environmental policy with George Busenberg (associate professor of environmental management and policy).

Bieganski: I also took classes with Monika Calef (professor of physical geography) on geographic information systems (GIS), which use computer technology to map out social, political, or environmental issues. In my senior capstone, I used GIS to create maps of the income disparities in Anaheim. If you look along the city boundary from west to east, you can see a clear distinction in income levels. Basically, the west part of the city has a lot of working class neighborhoods, Disneyland and the Anaheim Resort District are in the middle, and the wealth is concentrated in East Anaheim and Anaheim Hills. That’s just one specific way that the interdisciplinary approach at Soka helped enlighten me to different ways of seeing these issues. I’m now taking GIS classes in my master’s program in international affairs at UC San Diego.

What are your hopes for the impact of this research, both in the academic community and in the city of Anaheim and its future policies?

Burns: I would like students to be able to read this book in their undergraduate classes. We wrote it with undergraduates in mind. The book is chock-full of theoretical lessons about urban politics, who governs, and how they govern.

In terms of Anaheim itself, we’re in a third period of time in the relationship between Disneyland and the city. In the first period of this relationship, the city and the people who lived and worked there believed what Disneyland was saying about its value. In the second period, they questioned. And in the third period, the people fought back and set up some boundaries. Within those boundaries, Disney can ask the city for zoning changes; beyond them are things like getting subsidies and not paying taxes. If there’s a fourth period, it will either expand, narrow, or eliminate those boundaries.

Bieganski: One concept that comes up in the book is the social and political learning that the people of Anaheim underwent over the years. At first, residents didn’t know or have the tools to understand how revenue, taxes, and governance issues in Anaheim were affecting them. Over time, they learned. I think it shows the power of teaching people and awakening in them an understanding of what was going on in their communities and how this major international corporation was affecting them.

The book uses a theoretical framework of a changing political order to analyze Anaheim over time. It’s important to understand how things change. This book doesn’t see these political issues as static. It doesn’t assume that there will always be a coalition of wealthy or powerful people just because it’s been that way for a long time. Rather, the book shows that these things can change significantly or even reverse entirely. I think this book is very forward-looking in terms of politics in the 21st century and how cities deal with massive corporations in today’s world.